The Self

The Keys to (Lesbian) Camp

By Tiffany Harris

“I get that it’s a gay thing, but do you really need to wear your keys on your belt to a job interview?” my mother asked, gesturing to the carabiner on my belt loop that holds my keys. As someone who loses my belongings quite frequently, I no longer think much of the keys on my belt. To me, my carabiner serves as a functional and fashionable accessory that prevents me from getting locked out of the house. In my mother’s eyes, a “lesbian” stamp across the forehead would have sufficed. It had never crossed my mind to consider them as more than a practicality, but the forces of a patriarchal society have a way of imposing their rules on my body.

My carabiner is equal parts signifier and stereotype of lesbian sensibility, like my refusal of high heels and skirts or aversion to long nails. Hearing my keys clink and clatter as I walk has become one of many personal, subtle ways of sharing myself with the world—a way to rebel against heteronormative norms and customs. Lesbians breaking free from societal roles and playing with gendered expectations is a time-honored tradition; many lesbian stereotypes, symbols, and signifiers intentionally disrupt the concept of gender, speaking to its arbitrary nature.

Over the course of their lives, patriarchal power has rendered all bodies that are not white, cisgender, and male as objects. Women, especially, are treated entirely within the context of the body. Gender roles have provided an unspoken instruction manual on how to embody feminine traits to compliment the hypothetical man’s masculine and more “superior” qualities. The way we align and identify with gender is assumed to be an innate and inherent process; gender identity, however, is the direct result of socialization “where since birth every individual is made to fit into male or female categories adopting masculine or feminine roles, qualities and behaviour at any cost,” as asserted by Sabala and Meena Gopal in their 2010 study, Body, Gender, and Sexuality: Politics of Being and Belonging. 1

It is worth noting that these models are created under the assumption that anyone it applies to is straight. In the patriarchal imagination, anything that violates or contradicts this assumption, even moderately, is wrong. Lesbians, who constantly find themselves outcast from traditional norms of femininity, are forced to navigate and contend with a world that excludes them for excluding men.

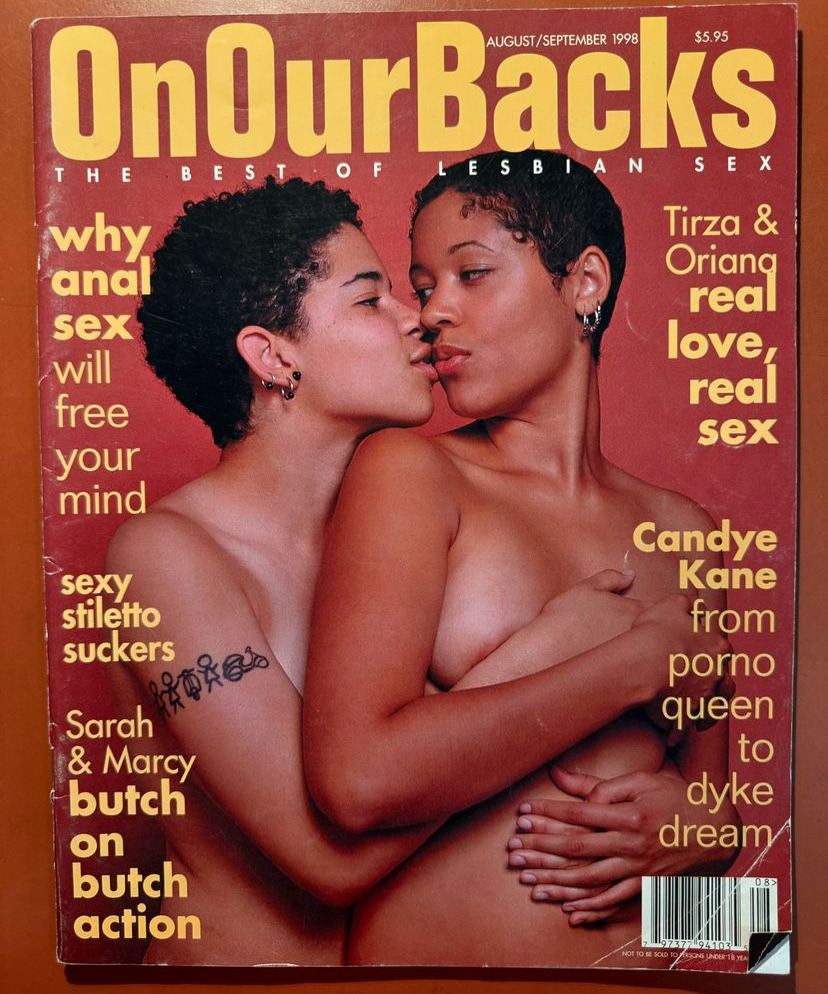

Lesbian Porn Magazine “On Our Backs,” August/September 1998 Edition, Cover Image.

Adrienne Rich claims that heterosexuality is an institution that makes many women—lesbian or otherwise—feel like they are compelled to center men in their personal and romantic lives. Heterosexuality, Rich maintains in “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” has been “forcibly and subliminally imposed on women.”2 The social sciences have asserted that the only normal and acceptable love is a heterosexual one and that men are necessary for the societal protection of women. As a result, any woman who does not subscribe to this model faces even further isolation in society.

This compulsive nature to heterosexuality, known as “compulsory heterosexuality,” is necessary to understanding lesbian identity. Lesbianism is anthithetical to the message that men are complementary to women and required for their survival, and to many, lesbian existence goes far beyond the margins of sexual orientation. Delineated by the total exclusion of men as both psychological and political practice, lesbian separatist strategy dictates that “just as lesbians can have real sex together without me, we can have real politics” as Betsy Brown states in Off Our Backs.3

One of several ways lesbians have been able to construct new meaning out of their identities is through gender—more specifically, gender’s roles and its artifice. This is where lesbian camp comes into play. The term “camp” derives from the French word se camper, meaning “to put oneself in a bold, provocative pose.” Camp exaggerates and over-emphasizes a theme or concept, and is less about making fun of something and more about finding and revealing the fun within something. I want to further assert the need to define the concept of “camp” within a lesbian-oriented framework, specifically one that includes Black lesbians.

Norms surrounding gender have especially been used to confine and define the body. As a Black lesbian, I find myself at constant odds with these norms. My key ring is not entirely a “gay thing” as my mother puts it (emphasis on entirely); my rule for my clothes is that they must be comfortable. Fashion is a realm that is defined by both individualism and conformity. Thus, a lot of personal and political power lies in the signifier—a beaconing signal to others that you are “one of them.” This is an especially important practice in lesbian circles.

Lesbian Rapper Young M.A. for PSD Underwear, photographed by Unknown

As Judy Grahn famously asserted in her 1984 novel Another Mother Tongue: Gay Words, Gay Worlds.4

“She may hang keys from her belt to signify, ‘I hold the keys.’ She may cut her hair very short … she may grow her hair very long and wear one earring only … or mismatched socks or other signs of asymmetry that say, ‘I cross over. I belong to more than one world” (Grahn, 1984).

Symbols such as these rest at a delicate balance between stereotype and signifier; the “lesbian uniform” that so many ascribe to is simply a means of connecting to those stereotypes and distorting them with intention. Performing the “look” of lesbian is to “play the part of The Lesbian but also insist on locating lesbianism within a contemporary setting, stomping out a path between lesbian histories and futures,” as explained by Mikaella Clements in an article for The Outline, “Notes on Dyke Camp.”5 While most literature and documentation on camp suggests the model only applies to gay men, Elly-Jay Nielsen contends that lesbian camp, in particular, takes on three main forms: the erotic, the radical, and as a form of critique.6 This mode of “queer expressivity,” “a clever act of subterfuge,” is a survival method that harkens back to an era where actions and behavior “were the only way to communicate a queer social identity.”

Lesbian camp is not just addressed by any one person or artifact. The music of lesbian rapper Young M.A. is filled with “legible signposts” that specifically translate into Black lesbian camp. On her hit single, “OOOUUU,” M.A. makes clear references to her gender (“My brother told me fuck ‘em get that money sis”) as well as her sexuality (”When you tired of your man, give me a call”). These lyrics speak to all three tenets of lesbian camp, particularly the erotic and the radical. Young M.A. uses her music, as well as her presentation, as a means to distance herself from “righteous queer politics and feminism,” as well as “the wholeness of hip-hop hegemonic masculinity,” as asserted by Saidah K. Isoke in “Thank God for Hip-Hop.”7 M.A.’s lyrics, often detailing her sexual exploits with other women, are not just a means of blending into the male-dominated realms of hip-hop music; her verses are an inherent act of resistance.

Young M.A.’s expression of her identity as a masculine lesbian allows her to assert dominance, as well as play with traditional notions of a masculine rapper. Masculine lesbians, especially Black ones, are a reminder that men do not have a patent on masculinity. The term “butch” describes a masculine lesbian who uses their body as a means of transcending the notions of gender and sexuality. As Kerry Manders wrote in a report for The New York Times, butch identity is a deliberate refusal of conventional gender and its aesthetics, a total disregard and rejection of the “confines of a sexualized and commodified femininity.”8

Already abjected from notions of traditional womanhood, lesbians are often and understandably estranged from femininity as well. This is especially true for Black masculine-presenting lesbians who have terms and identities all their own concerning womanhood and gender. The term “stud,” for example, is used to define a masculine lesbian beyond the standard butch definition—a stud is specifically and explicitly Black. In a world defined by heteronormative, white standards, it is inherently radical to be Black, lesbian, and masculine all at once: “Black women in general are not seen, so black butchness tends to be doubly invisible. Except for studs: They’re very visible,” said Roxane Gay to The New York Times.9

As mainstream lesbianism is notably white, this makes the signifiers of lesbianism notably white, too. The Doc Marten boot has long been a symbol used by queer women, a stereotype that lesbians are partial to sensible, practical footwear. This dedication to wearing items of comfort, over items of conformity, is another assertion of lesbian camp. Thus as definitions of camp expand, it is necessary to locate markers of lesbian camp as they apply to Black individuals. Who says the Timberland work boot, a staple in black lesbian fashion, is not its own form of sensible lesbian footwear?

Camp sensibility for lesbians, will always be a political statement; if the personal is political then the body (and how it is dressed) is a radical concept. Perhaps the biggest reason lesbian camp has not been asserted in scholarly discourse is because it is not well understood. Most times, lesbian camp pokes fun at the futility of gender roles, exaggerating them so they yield more personal benefit. But lesbian camp is more than an imitation or parody of the constructs that men have forced themselves into. Lesbian camp takes what is real to us, internally, and transforms it into something external and recognizable. My key ring, although a small symbol, signals to others that my life does not center the likes of men. The signifiers and stereotypes of lesbian camp are defined for and by other lesbians, and if my key ring helps others know who “wears the keys” in my life, I am more than happy to hold them.

•

Edited by Ava Emilione

1 Sabala, and Meena Gopal. “Body, Gender and Sexuality: Politics of Being and Belonging.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 45, no. 17, 24-30 April 2010, pp. 43-51. Economic and Political Weekly.

2 Rich, Adrienne Cecile. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.” Journal of Women’s History, vol. 15, no. 3, Johns Hopkins University Press, Autumn 2003.

3 “Activism Works Because We Do.” Off Our Backs, vol. 25, no. 11, Dec. 1995, pp. 8-10. Off Our Backs, Inc., www.jstor.org/stable/20835333.

4 Grahn, Judy. Another Mother Tongue: Gay Words, Gay Worlds. Beacon Press, 1984.

5 Kornhaber, Spencer. “Notes on Dyke Camp.” The Outline, 8 June 2018, https://theoutline.com/post/4556/notes-on-dyke-camp?utm_source=contributor_pages.

6 Nielsen, Elly-Jean. “Lesbian Camp: An Unearthing.” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, 2016, pp. 116-135. DOI: 10.1080/10894160.2015.1046040.

7 Isoke, Saidah. “Thank God for Hip-hop”: Black Female Masculinity in Hip-hop Culture . 2017. Ohio State University, Master’s thesis. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center, http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?

8 Manders, Kelly. “The Renegades.” The New York Times, 13 Apr. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/13/t-magazine/butch-stud-lesbian.html.

9 Ibid.